May 4th, 1961, thirteen brave individuals boarded two buses in Washington, DC with the goal of traveling through the Deep Jim Crow South to New Orleans, to test the 1960 Supreme Court ruling of Boynton v. Virginia, which declared segregated facilities for interstate passengers illegal.

The “Freedom Rides” were initiated by the civil rights organization, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). CORE was founded on the principle of nonviolent protest and its director, James Farmer, said the purpose of the Freedom Rides was “to create a crisis so that the federal government would be compelled to enforce the law.”

The “original” 13 consisted of seven black people and 6 whites. The riders had received training in reacting nonviolently in volatile situations with the intent of showcasing “the contrast between your dignified, disciplined confrontation of the wrong and then the reaction of the violence.”

The first part of the journey South was not met with much confrontation, that is until the riders arrived in Alabama where the Police Commissioner (and segregationist) Bull Connor and police sergeant (and KKK supporter) Tom Cook, organized violence against the riders with other Klan members. These terrorists were given a 15 minute window to attack the Freedom Riders without being arrested once they arrived in Anniston, AL, finishing the assault in Birmingham.

On May 14th, 1961..Mother’s Day no less, the first of two buses was attacked in Anniston by the Klan, some still in their church clothes. They slashed the tires of the bus and threw a firebomb on board while forcing the doors shut in hopes of burning everyone alive. Keep in mind, the police allowed this. They were willing to kill Black and white people to preserve superiority over a race of people who just wanted access to the same restrooms, waiting rooms, and restaurants as them. This was a murderous offense in their eyes. Oh white people. The mob scattered after shots were fired, allowing the riders to exit the bus, where they were beaten.

The second bus was boarded by Klansmen who beat the riders senseless. When the bus arrived in Birmingham, the riders were viciously attacked by racist mob, who had carte blanche in beating them thanks to Bull Connor.

Upon hearing about yet another mob forming in Montgomery, AL, the bus drivers refused to drive the Freedom Riders any further. Bloody and beaten, the remainder of the trip was called off and the Freedom Riders were flown to their final destination in New Orleans.

News of the abuse of these riders traveled quickly, achieving the intended goal of shining light on the fact that the South refused to abide by the laws forcing desegregation and that the federal government was unwilling to enforce it.

The movement though, could not end there. It would be a set back if they were to stop. So Diane Nash, a civil rights activist and leader of the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), reached out to James Lawson, a minister and activist who began weekly nonviolent workshops in 1959 with the intent of using it as a tool to fight against segregation, regarding not allowing the freedom rides to stop because of violence waged at them by their opponents. Nash touched base with Dr. Martin Luther King and James Farmer and told them that Nashville Student Movement was going to take up the task.

James Lawson’s mug shot

So the Nashville movement took it on ourselves to do that. Chances are — and I’ll speculate here — if we hadn’t done that, it would have been quite some time before any major activity took place to ignite the movement again. If the rides had stopped, it would have been seen as a defeat. It would have been off the front pages. Whether or not the Kennedy Administration would have been as forceful in demanding that the Interstate Commerce Commission tell the states and the businesses that segregated interstate travel had to end, I don’t know. – James Lawson

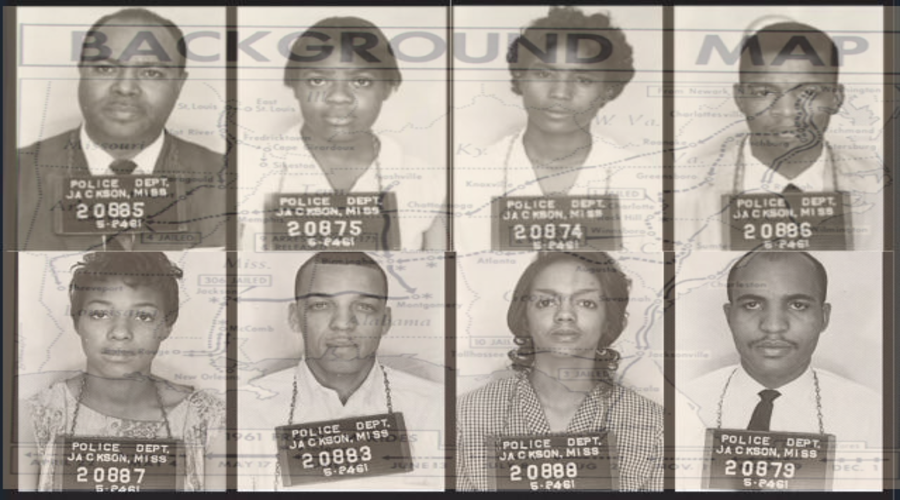

On May 17th, 10 students from the Nashville Student Movement took a bus to Birmingham, where they were arrested and jailed. On May 20th, Freedom Riders reached Montgomery, AL, where they were beaten with impunity. On May 22nd, more Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery to continue the rides in place of the injured and wounded riders, with their sights set on Mississippi.

In an attempt to quell the violence, but not upset his southern constituents, the Kennedy Administration made a deal with the governors of Alabama and Mississippi for them to provide state police and National Guard protection of the Freedom Riders and in return the Feds would not intervene in the arresting of the Freedom Riders once they attempted to violate segregation spaces.

For a period of months, over 400 Freedom Riders were arrested. Many spent almost 2 months in Mississippi’s worst prison, Parchman. Civil Rights activists John Lewis and Stokely Carmichael were included in those arrests.

John Lewis

Stokely Carmichael

At the time, the Freedom Riders were actually seen as unpatriotic because the damage they caused to America’s reputation.

David Brinkley did a commentary on the NBC Nightly News. He, of course, was from North Carolina. He considered himself to be a moderate liberal, certainly someone who didn’t normally endorse Jim Crow segregation. But he felt that the Freedom Riders were being unreasonable. And he was not alone in this.

There were a number of sort of mainstream, many mainstream journalists who were supported by the public opinion polls. In general, more than two-thirds of Americans, although they supported the ideal of desegregation in most cases, rejected the tactics of the Freedom Riders. And Brinkley was speaking for them, suggesting that there was something unpatriotic about what the Freedom Riders were doing by not recognizing the damage that they were doing to America’s reputation, to its image around the world.

And yet they persistent. For seven months, multiple waves of Freedom Riders continued to make their journey to integrate Southern bus facilities. Volunteers came from over 40 states. Half were Black. A quarter of them were women. Most were between the ages of 18 and 30.

On November 1, 1961, Attorney General Robert Kennedy made the Interstate Commerce Commission, the former independent agency of the U.S. government, established in 1887 that was charged with regulating the economics and services of specified carriers engaged in transportation between states, issue “tough” regulations and fines against bus facilities that continued to racially segregate, eventually leading to the end of segregation at public bus facilities.

But none of this would be possible with out the courage of all of those who were willing to put their livilihood and lives on the line to fight for equality and against injustice. Whether the non-violence method was the appropriate response can be debated at a later date. Today we celebrate these trailblazers, who did what was right, even if it was considered unpopular. Some of them were expelled from college for participating. Some lost their jobs. Others are still missing.

View this post on Instagram

America, in particular white Americans, like to believe that American roots are far removed from this level of hate, as if there aren’t people still alive who participated in these events (See: John Lewis). Those who beat and burned, and killed Black people and went unpunished were able to continue their jobs where they probably discriminated against Black people. They were able to raised children to probably discriminate against Black people. They were able to run for office to create legislations that can target and discriminate against Black people. This hatred is woven int the fabric of the American flag they pledge allegiance to. Never let them forget what an embarrassment this country was and continues to be.

Also, ask yourself would you have the strength to do what these heroes did? Would you genuinely fight for the cause? Would you risk everything to make a change? The time is now to continue the work of the past, but this time more aggressively. Let’s get uncomfortable.

Salute