On October 16th, 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two Black American track and field stars, stood on the Olympic podiums to receive their medals and made a statement that resonated through sports, this country, and the world. It is one of the most iconic moments in sports history, Black history, and American history…and it almost didn’t happen.

Take a trip with me.

From International Socialist Review:

In the fall of 1967, amateur Black athletes formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) to organize an African American boycott of the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. OPHR, its lead organizer Dr. Harry Edwards, and its primary athletic spokespeople 200-meter star Tommie Smith and 400-meter sprinter Lee Evans were very influenced by the Black Freedom struggle. Their goal was nothing less than to expose how the U.S. used Black athletes to project a lie both at home and internationally.

In the founding statement of OPHR, they wrote:

We must no longer allow this country to use … a few “Negroes” to point out to the world how much progress she has made in solving her racial problems when the oppression of Afro-Americans is greater than it ever was. We must no longer allow the Sports World to pat itself on the back as a citadel of racial justice when the racial injustices of the sports industry are infamously legendary…. [A]ny black person who allows himself to be used in the above matter…. is a traitor to his country because he allows racist whites the luxury of resting assured that those black people in the ghettos are there because that is where they want to be…. So we ask why should we run in Mexico only to crawl home?

One of the first to get on board with OPHR was Lew Alcindor. Later known as Kareem Abdul?–Jabbar, Alcindor was at the time the most prominent college athlete in the United States. Alcindor dominated the basketball world as the center for John Wooden’s dynastic UCLA Bruins teams. Alcindor told Sports Illustrated why he was joining the revolt:

I got more and more lonely and more and more hurt by all the prejudice and finally I made a decision:… I pushed to the back of my mind all the normalcies of college life and dug down deep into my black studies and religious studies. I withdrew to find myself. I made no attempt to integrate. I was consumed and obsessed by my interest in the black man, in Black Power, black pride, black courage. That, for me, would suffice. I was full of serious ideas. I could see the whole transition of the black man and his history. And I developed my first interest in Islam.

Harry Edwards, lecturer at San Jose State University who called for a boycott of the Olympic Games in Mexico City by African Amercian athletes, talks with Tommie Smith (left) and John Carlos (right)

OPHR had five central demands:

• Restore Muhammad Ali’s title. Ali had been stripped of his title in June 1967 for his refusal to fight in Vietnam.

• Remove Avery Brundage as head of the United States Olympic Committee. Brundage was a notorious white supremacist best remembered today for sealing the deal on Hitler hosting the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. He once praised Hitler’s regime at a rally in Madison Square Garden. As head of the International Olympic Committee, he also opposed the entry of women as competitors.

• Disinvite South Africa and Rhodesia. This was a conscious effort to express internationalism with the black liberation struggles occurring in these two apartheid states.

• Boycott the New York Athletic Club.

• Hire More Black Coaches.

The boycott became a national debate. California Governor Ronald Reagan had harsh words for the plan: “I disapprove greatly of what Edwards is trying to accomplish. Edwards is contributing nothing toward harmony between the races.” (Reagan’s statement was indirectly profoundly offensive to people like Smith, Evans, and Alcindor, who resented being represented as Edwards’ puppet.) Edwards responded to Reagan by calling him “a petrified pig, unfit to govern.”

Jackie Robinson expresses support for the 1968 Olympic boycott movement led by Black athletes and activists

But the boycott received support from none other than Jackie Robinson, who said, “I do support the individuals who decided to make the sacrifice by giving up the chance to win an Olympic medal. I respect their courage. We need to understand the reason and frustration behind these protests… it was different in my day, perhaps we lacked courage.”

The boycott also received solidarity and support from Dr. King in the months before his death. His spokesman Andrew Young said:

Dr. King applauds this new sensitivity among Negro athletes and public figures and he feels that this should be encouraged. Dr. King told me this represents a new spirit of concern on the part of successful Negroes for those who remain impoverished. Negro athletes may be treated with adulation during their Olympic careers, but many will face later the same slights experienced by other Negroes.

Momentum built throughout the year. The assassination of Dr. King in April shook some of the stalwart anti-boycott athletes. Ralph Boston, the most prominent track and field star, said, “For the first time since the talks about the boycott began, I feel that I have a valid reason to boycott.” He went on to explain how he came to this realization:

I sat and thought about it and I see that if I go to Mexico City and represent the United States I would be representing people like the one that killed Dr. King. And there are more people like that. On the other hand, I feel if I don’t go and someone else wins the medal and it goes to another country, I haven’t accomplished anything either. It is disturbing when a guy cannot even talk to people and he is shot for that. It makes you think that Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown are right. All my life I felt that violence wasn’t the way to deal with the problem. How do you keep feeling this way when things like that keep coming? How?

H. Rap Brown, John Carlos, Harry Edwards and Stokely Carmichael hold a press conference at Howard University in Washington, D.C., about the Olympic Project for Human Rights, a boycott of the Olympics, in October 1968. The Olympics were held Oct. 12-27

A boycott looked like a possibility, but it was not to be. The wind went out of its sails for myriad reasons. Some felt threatened by Brundage’s stern warning, “If these boys are serious, they’re making a very bad mistake. If they’re not serious and they’re using the Olympic Games for publicity purposes, we don’t like it.” Others felt that just raising the issues was enough. But most centrally the insoluble problem was that athletes who had trained their whole lives for their Olympic moment quite understandably didn’t want to give it up.

One person who was not there, it must be noted, was Lew Alcindor, who staged his own one-person boycott and stayed home.

This effort to silence them came in different forms—even in the form of track legend Jesse Owens, whom Brundage sent to discredit the Olympic rebels.Owens wasn’t the only Black athletic legend to come down on OPHR. His “other half” from the 1930s had something to say as well. As the Washington Afro–American reported: “Joe Louis says colored athletes should consider themselves Americans first and colored Americans second and disagrees with those pushing for a boycott. ‘Whenever you have a chance to do something for your country you should do it,’ Louis said.”

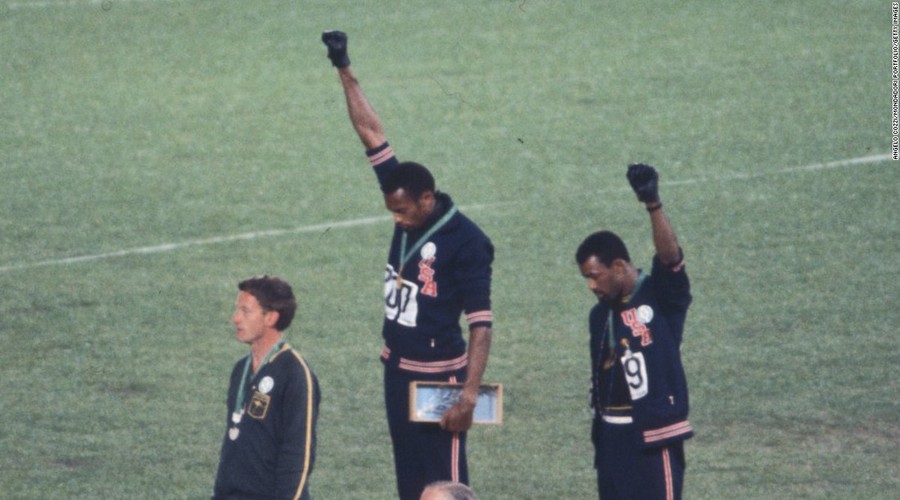

It was on the second day that Smith and Carlos took their stand. First Smith set a world record in winning the 200-meter gold and Carlos won the bronze. Smith then took out the black gloves. When the silver medalist, a runner from Australia named Peter Norman, saw what was happening, he affixed an OPHR button to his chest to show his solidarity on the medal stand. As the U.S. flag began rising up the flagpole and the anthem played, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their fists in a Black power salute. But there was more to their protest than the gloves. The two men also wore no shoes to protest Black poverty and beads to protest lynching. Within hours, Smith and Carlos were expelled from the Olympic Village. Avery Brundage justified this by saying, “They violated one of the basic principles of the Olympic games: that politics play no part whatsoever in them.”

Ironically, it was Brundage’s reaction that really spurred the protest into the limelight. As Red Smith, wrote, “By throwing a fit over the incident, suspending the young men and ordering them out of Mexico, the badgers multiplied the impact of the protest a hundred fold.”

But Brundage was not alone in his furious reaction. The Los Angeles Times accused Smith and Carlos of a “Nazi-like salute.” On the Olympic logo, in place of the motto “Faster, Higher, Stronger,” Time magazine blared “Angrier, Nastier, Uglier.” The Chicago Tribune called the act “an embarrassment visited upon the country,” an “act contemptuous of the United States,” and “an insult to their countrymen.” Smith and Carlos were “renegades” who would come home to be “greeted as heroes by fellow extremists.”

But for Smith and Carlos there were no regrets. Carlos was clear on why he had to act.

I was with Dr. King ten days before he died. He told me he was sent a bullet in the mail with his name on it. I remember looking in his eyes to see if there was any fear, and there was none. He didn’t have any fear. He had love and that in itself changed my life in terms of how I would go into battle. I would never have fear for my opponent, but love for the people I was fighting for. That’s why if you look at the picture [of the raised fist] Tommie has his jacket zipped up, and Peter Norman has his jacket zipped up, but mine was open. I was representing shift workers, blue-collar people, and the underdogs. That’s why my shirt was open. Those are the people whose contributions to society are so important but don’t get recognized.

Upon returning home, there was support for Smith and Carlos in the Black community, but not the entire Black community. Carlos explains: “There was pride but only from the less fortunate. What could they do but show their pride? But we had Black businessmen, we had Black political caucuses, and they never embraced Tommie Smith or John Carlos.

Smith and Carlos’ efforts are immortal as a moment when the privileges of athletic glory were proudly trashed for a greater goal.

|