TL;DR: Black people were not impacted the same as Whites during the 1918 flu pandemic however we are more vulnerable now. The low death rate for Blacks during the 1918 pandemic is partially due to segregation which kept our exposures limited due to “defacto” quarantines. Also, segregation meant that there were Black-run hospitals and healthcare organizations that catered specifically to the health and wellness of Black people at a time when healthcare accessibility was either extremely limited and/or non-existent. Now, post-Jim Crow, Black communities are still fighting against poverty and healthcare disparities but without those institutions designed specifically to protect us. This, compounded with minimal COVID.-19 testing and data for our communities, means one thing… it’s open season.

The majority of the information from this article was gathered from the 2010 Public Health Report titled There Wasn’t a Lot of Comforts in Those Days:” African Americans, Public Health, and the 1918 Influenza Epidemic from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, US National Library of Medicine. If it is not cited specifically then it probably came from here.

In 1918, the entire world was devastated by the 1918 flu pandemic. Spreading worldwide from 1918 through 1919, this flu took the lives of approximately 50 million people across the globe. 675,000 of those lives lost were American. The 1918 flu pandemic hit in three waves. The first wave began in Spring 1918 thanks to the mass troop movement of thousands of US soldiers engaged in World War I. The second wave began in Fall 1918, which was responsible for most of the pandemics deaths. The third wave was in Winter 1918/Spring 1919, adding to the pandemics overall death toll.

During this 1918 epidemic that took the lives of MILLIONS, the death rate for Black Americans was relatively low (please note: similar to 2020, finding the breakdown of 1918 flu infections and death rates by race was not accessible to me when this article was published). Based on this information, it is easy to surmise that history would repeat itself and that Black Americans are able to withstand the flu better than our counterparts of other races. Black folks even Kiki’d when news about COVID-19 began to spread with memes flying out about how none of its victims were Black. Some even foolishly believed that Black people were immune from getting it all together. These false narratives applied with the misleading data from 1918 could result in our demise.

Early COVID-19 data shows Black people are contracting and dying from COVID-19 at an alarming rate. In Chicago, 70% of COVID-19 deaths are Black even though Black people only make up 30% of the city’s population. In Milwaukee County, 81% of COVID-19 deaths are Black even though it’s only 27% Black. The state of Michigan’s Black population is only 14% yet Blacks make up 40% of the state’s deaths. Los Angeles County is only 9% Black but account for 17% of the County’s COVID-19 deaths. Unfortunately we won’t know the full devastation until much later, if ever, because the federal government, along with most states, are not releasing data on the race or ethnicity of people who have tested positive for the virus, creating a “information gap that could aggravate existing health disparates and prevent cities and states from equitably distributing medical resources and potentially violate the law.”

All this is compounded with the lack of equal and accessible health care in Black communities thanks to poverty and red-lining, the result of 400 years of systematic racism and oppression. This leaves Black people more vulnerable for underlining health issues such as asthma, heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes. One must also factor in our distrust of the medical community, thanks to the Tuskegee Experiment. Black Americans have a rightful skepticism of the medical community which does n’t help.

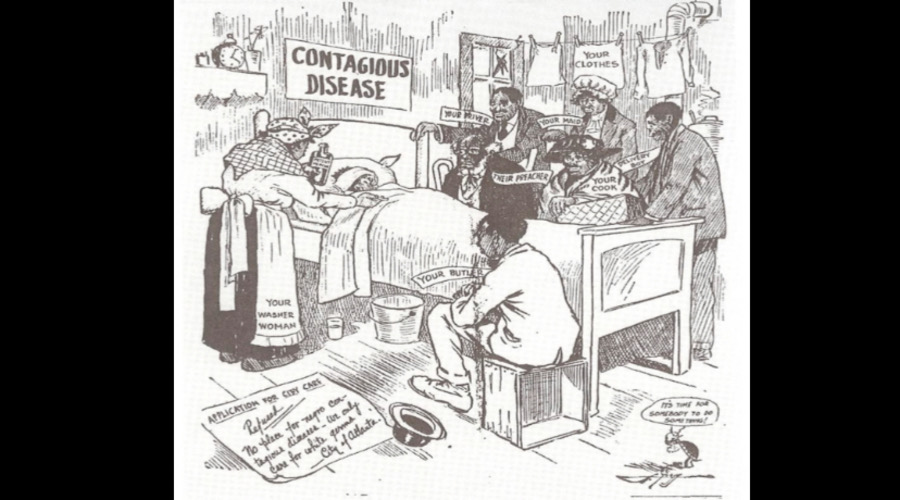

Similar to 2020, Black communities of 1918 were already plagued by “public health, medical, and social problems, including racist theories of Black biological inferiority, racial barriers in medicine, and public health, and poor heath status”. According to medical and public health reports, Blacks in 1918’s America had higher morbidity and mortality rates with the death rate of Blacks exceeding that of Whites by 69%. Blacks were two to three times more likely to die from tuberculosis, pneumonia, and diarrheal disease but had lower death rates for scarlet fever, cancer, and liver disease.

This research was conducted by activist and sociologist W.E.B. DuBois titled The Health and Physique of the Negro American. In this, DuBois documented the poor health status of Blacks and the underlying causes which DuBois attributed to social conditions, not race, which was the was the accepted (and very White) science of the time. See, back then, a statistician for Prudential Life Insurance (yep THAT one) by the name of Frederick L. Hoffman claimed in his very influential treatise Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, that Black mortality rates were not due to conditions of life but that of race. Luckily Black people, while taken as simpletons, were never actually simple.

C.V. Roman, M.D. was a doctor and founding member of the Journal of the National Medical Association, an organ of Black physician organizations, founded in 1908. In 1917, Roman stated “All history shows that ignorance, poverty, and oppression are enemies of health and longevity.” Racism and Jim Crow made health care access to the vulnerable Black population almost impossible. This led to hospitals created for Black people, by Black people, which ensured, to some level, that our people received proper health care based on need, not race. Black medical professionals pushed for sanitation laws to clean up and improve Black neighborhoods as well as create programs to teach about personal hygiene and sanitation and sought to increase the number of medical facilities open to Black patients. This was a driving force for Black communities during the 1918 Flu pandemic.

These medical facilities did more than just provide healthcare access for Black patients. They also provided employment and training opportunities for Black healthcare workers. Here is a a non-comprehensive timeline of Black-run hospitals and medical organizations/associations leading to the 1918 Flu Epidemic:

1862 – Freedman’s Hospital was established 1862 in Washington, DC by the Medical Division of the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide the much needed medical care to slaves, especially those freed following the aftermath of the Civil War. Today it is know as Howard University Hospital and is one of only two remaining traditional Black hospitals.

1886 – Saint Agnes Hospital was established in Raleigh, NC. It was referred to in 1922 as the “only well equipped hospital for Negroes between Washington and New Orleans, serving not only North Carolina, but adjacent Virginia and South Carolina.”

1886 – Black Physicians created the Loan Star State Medical, Dental, and Pharmaceutical Association of Texas.

1887 – Old North State Medical Society of North Carolina, the oldest medical society for African American Physicians in the United States, was established.

1891- Daniel Hale Williams, a prominent Black surgeon, opened Provident Hospital in Chicago, IL, the nation’s first Black-controlled hospital. It is now a public hospital.

1892 – Tuskegee Institute Hospital & Training School opened. It was the first Black hospital in Alabama.

1895 – Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School was established in Philadelphia, PA by Dr. Nathan F. Mossell, a Black doctor. The hospital was originally funded by Philadelphia’s Black community.

1895 – National Medical Association was founded, the oldest and largest national organization representing Black physicians and their patients in the country.

1903 – The Women’s Improvement Club, a Black women’s organization, was established. They led Black anti-tuberculosis efforts and. hosted outdoor camps for Black children with tuberculosis. They also sponsored lectures on hygiene and prevention of tuberculosis.

1906 – Burt Home Infirmary was established by Dr. Robert T. Burt in Clarksville, TN. It was Clarksville’s first and only hospital until 1916.

1908 – National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses was founded by Martha Minerva Frankin.

1915 – National Negro Health Week was established by Black activist and educator Booker T. Washington with the goal to teach Black people “about the principles of public health and hygiene to help them become stronger and more economically productive.” National Negro Health Week was successfully held in 16 states and by 1925 it was hosted in 139 Black communities across the country.

By 1944, there were 124 Black Hospitals in the United States. Twenty-three of them were accredited by the American College of Surgeons. These hospitals were located in 23 states and the District of Columbia. Today, only two are still standing: Howard University Hospital in Washington, DC and Riverside General Hospital in Houston, TX.

And herein lies the curse of integration we do not like to talk about. Integration, as necessary as it was, made “For-Blacks” obsolete. We didn’t “need” For-Blacks hospitals post-integration because now we weren’t prohibited from going to White hospitals. EXCEPT that the Black hospitals knew how to treat Black patients and address our needs based on an understanding of our environment, something sorely missing from our health care community today. Now, in 2020, the disparities in health care for Black people exist because we no longer have our own institutions who can educated and protected us.

During the 1918 flu pandemic, Blacks mobilized to help one another. It was truly a “it takes a village” mentality. In Kentucky, Black women volunteered to lead relief activities and provide care to victims and cleaned their homes. Black home economics teachers volunteered to cook at food centers, schools, hospitals, and nurseries. The National Urban League, a civil rights organization, hired and trained nurses in Columbus, OH to provide free care for flu patients. The Chicago branch organized care for flu patients in their homes. They National Urban League also allowed the Red Cross to use its offices to distribute food in Black communities.

When the beds filled up at Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia, its medical director established an emergency annex on the first floor of a Black parochial school. In another city, a Black hospital was established at a local elementary school so that Black patients could be treated by Black medical professionals instead of at segregated hospitals where they were seen in a basement…if they were even able to receive treatment at all. Integration helped dismantle the pipelines our communities required to properly address our needs which are consistently ignored by the overall medical community.

This next statement may ruffle a few feathers but fuck it. Integration may also be a reason why COVID-19 is hitting Black communities harder than the 1918 flu pandemic. Hear me out. It was heavily reported by Black news publications that the 1918 flu was not affecting Black communities the same as whites. Medical professionals were stumped as to how Blacks, who typically died more often than than whites from pneumonia and flu, and lived in conditions that would be more favorable to the spread of the disease, death rates were not as high. From 1900-1917 influenza deaths in industrial policy holders covered by Metropolitan Life Insurance Company found that Black women (age 20-45) and Black men (age 20-55) had higher death rates than whites. But during the 1918 pandemic, the Black death rate dropped lower than that of whites. Segregation is suspected as a factor in this drop in Black death rates because segregation enacted a “defacto’ quarantine that limited our exposure to the virus. That “protection” does not exist anymore.

Other factors attributing to the low death rate numbers of Blacks during the 1918 flu pandemic is that there was a lack of accurate data collection and many Black cases may have been underreported because of inadequate access to health care. Sound familiar? To this day, it is still unclear as to why the Black population was not as affected by the 1918 flu pandemic. The Philadelphia Board of Health reported 12,687 deaths from September 20-November 8, 1918. Of those, only 812 were Black.

After the pandemic subsided, Blacks remained segregated in the medical field. All the optimism built from Black doctors working besides White doctors against a common enemy dissipated. This pandemic did not lead to the development of any major public health policies to improve the poor health status of Blacks and did not stop whites from spreading their racist, and unfounded, scientific theories about the supposed inferiority of the Black race. Life for Black people went back to normal, which wasn’t a good thing.

That leads us to today. 2020. Where COVID-19 is steamrolling through our immune systems, snatching the lives of our elders, our families, our people. It is bad enough having a target on our backs as is, being Black in America. Try convincing Black men that it is safer for them to wear a mask over their face in public…the same public where Karen calls the cops on you for being in said public spaces and trigger happy police who shoot first and ask questions later.

In order to survive this, we must mobilize for each other. We must pool together our resources and help one another. Our Black healthcare workers must create strong networks in order to educate Black people on what we can do to live healthier lives but we also have to help them, just like we did for each other in 1918. Our organizations and religious institutions need to make Black health care a priority. And not like THIS. We have to rebuild our segregated ingenuity within our integrated spaces. We need Black hospitals, out-patient facilities, mental health clinics, nutritionists, and the likes.

And for those wondering HoW aRe We GoInG tO pAy It? Well its layered. WE need to do a better job of investing in our own. We celebrate Black celebrities for achieving wealth and then watch that wealth be spent benefiting white spaces. The Black elite need to do a better job of giving back and break the cycle of believing “making it” means leaving behind and/or forgetting where you came from. They have the resources to do more, so do it. Secondly, reparations. Reparations should be used to fund public health initiatives specifically for Black people. If Congress can pull $2.5 trillion stimulus package out its ass in a matter of weeks then it can add a multibillion dollar line item to fund programs that specifically impact Black communities.

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, is that if we don’t start looking out for each other, it’s open season. I am sad to say that this is just the dress rehearsal. Lets be ready for the next round. Because, lets face it, we know it’s coming and we know it’s only going to get worse. And if history has taught us anything it is that we, BLACK PEOPLE, won’t get anywhere if we do not do it ourselves. We are all we got. Let’s get to work!